Holy Fool and Gambler

„Weinberg uses leitmotifs in the manner of Wagner, thereby taming the wealth of characters and narrative twists and turns.“

In Prokofiev’s Gamblerand Weinberg’s Idiot, Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s broken characters also reflect our present time.

“At the scaffold there is a ladder, and just there he burst into tears – and this was a strong man, and a terribly wicked one, they say! […] At last he began to mount the steps; his legs were tied, so that he had to take very small steps. The priest, who seemed to be a wise man, had stopped talking now, and only held the cross for the wretched fellow to kiss. At the foot of the ladder he had been pale enough; but when he set foot on the scaffold at the top, his face suddenly became the colour of paper, positively like white notepaper. His legs must have become suddenly feeble and helpless, and he felt a choking in his throat – you know the sudden feeling one has in moments of terrible fear, when one does not lose one’s wits, but is absolutely powerless to move? If some dreadful thing were suddenly to happen; if a house were just about to fall on one; don’t you know how one would long to sit down and shut one’s eyes and wait, and wait?”

In Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novel The Idiot, written in the late 1860s, the young Prince Lev Nikolayevich Myshkin describes an execution he witnessed in Lyon. The scene is autobiographical to a horrifying degree: on 22 December 1849, every measure had been taken to execute the death sentence a Tsarist military tribunal had passed against the author, who was 28 at the time.

As members of the early socialist Petrashevsky Circle, Dostoyevsky and his fellow defendants had been found guilty of plotting to topple the ruling order. Only when the first three delinquents had already been shackled to their stakes, wearing white shrouds with sacks over their heads, and the firing squad had already taken aim was the order pardoning them – which had long been received – read out: Dostoyevsky’s sentence was commuted to eight years of hard camp labour. Stefan Zweig featured Dostoyevsky’s near-death experience in his Sternstunden der Menschheit in poetic form. After the announcement of the redeeming message – which no one understands at the moment to also mean years of unspeakable suffering – it says there: “His soul glowed after torture and wounds / And he understood, / That in this one second, / He was that other, / Who stood at the cross a thousand years ago, / And that he, like Him, / Since that burning kiss of death / Must love life for its suffering.”

Russian Fates. Dostoyevsky survived four years in Siberia before he had to serve as a soldier – as part of his pardon. In 1857, he married a friend’s widow (who died of tuberculosis as early as 1864) and also had his civil rights reinstated; his epilepsy now began to manifest grave symptoms, getting him dismissed from the military in 1859. Dostoyevsky’s The House of the Dead was the first literary witness to the inhuman conditions prevalent in Russian penal colonies: operagoers are familiar with the work from Leoš Janáček’s setting of 1930. First and foremost, however, Dostoyevsky achieved literary fame because his depictions of morals in 19th-century Russia and Europe were able to illuminate even the darkest corners of the human psyche. Voluminous novels such as Crime and Punishment, The Demons or The Brothers Karamazov, consumable because of their genesis as serialized novels, with short arcs of tension, were eminently readable and often adapted as screenplays, earning him a reputation as a breath-takingly precise surveyor of the human soul – a reputation which has not faded today, but has only been reinforced.

Incidentally, Zweig’s Sternstunden der Menschheit, that collection of great deeds and failures, turning points, coincidences and fateful moments, will be staged this summer as part of the Salzburg Festival’s drama offerings. The opera programme, however, will be marked by two works based on Dostoyevsky’s epochal epics: The Gambler by Sergey Prokofiev and The Idiot, composed by Mieczysław Weinberg. One fascinating aspect is how many adventurous, sometimes even life-threatening fragmentations and shifts dominated the biographies of these two composers, making them resemble Dostoyevsky’s. His Prince Myshkin, the title character of The Idiot, is something akin to a Holy Fool, whose goodness of heart means he is failed both by his own intentions and humanity itself.

Myshkin might be described as a man who is always somehow in the wrong place, which is also true in a way for Mieczysław Weinberg (1919-1996). The son of a Polish-Jewish family of musicians had to flee the Nazis twice: once, on foot, from his hometown of Warsaw to Belarus, then from Minsk by train to Tashkent, 3,000 kilometres away. It was mere coincidence that he then managed to escape Stalin as well: in 1953, Weinberg, who was then in Moscow and a close friend and colleague of Dmitri Shostakovich, was arrested and tortured, but after the dictator’s death a few months later, he was surprisingly set free again. During the past decade or two, Weinberg is being increasingly rediscovered as a kind of musical brother of Shostakovich, yet with his own profile.

Leitmotifs and a Technique of Cuts. “Weinberg’s biography is fascinating, oppressive, tragic – and at the same time, it almost resembles a biography of the 20th century and its totalitarianisms: all his life, he was basically a refugee in flight,” says Markus Hinterhäuser. Even while still the artistic director of the Wiener Festwochen, he championed Weinberg’s operas and concert works, and he now reaffirms this at the Salzburg Festival. “In Weinberg’s works, there are many clear and also moving references to his biography – but also the exact opposite, almost a musical liberation from this life and its circumstances,” Hinterhäuser explains. Especially for composers who lived in the Soviet Union, the political and historical context is essential for an understanding of their music – with consequences and echoes into the present, which is different, yet has its similarities: “What could they, what were they allowed to compose? Which encryptions were there, which kinds of messages were conveyed? Many are quick to judge, but often these oversimplifications fail to do justice to the circumstances.”

One conductor who started studying Weinberg early on is Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, born in Lithuania in 1986, whose star has been rising rapidly during recent years and who makes her debut conducting the Vienna Philharmonic in this opera production. Gidon Kremer had brought her attention to Weinberg’s oeuvre, and starting with the late chamber symphonies, she developed something akin to an addiction to Weinberg’s compositions – and with Dostoyevsky’s writing. “For most of his books, during the first fifty or one hundred pages, one tries to find some orientation amidst the onslaught of names, places and events; but gradually the strands of the story are interwoven more and more closely, and after that one hundredth page, the story develops such a pull that you just can’t stop reading anymore.” The audience might feel the same way about Weinberg’s seventh and last opera, written in 1986/87. The piece begins with a symbolic sound: interspersed with fateful-metallic bass notes, a whistle signal, the screeching of tires and the scream of a wounded soul immediately coagulate in a chord that put one’s teeth on edge, several times. As if one couldn’t take one’s eyes off a horrible abyss, feeling drawn into its lethal depths over and over. “That is the motif of desperation,” the conductor explains. “Weinberg uses leitmotifs in the manner of Wagner, thereby taming the wealth of characters and narrative twists and turns. However, he combines it with a technique of rapid cuts, a technique he acquired during his rich experience as a composer of film scores.”

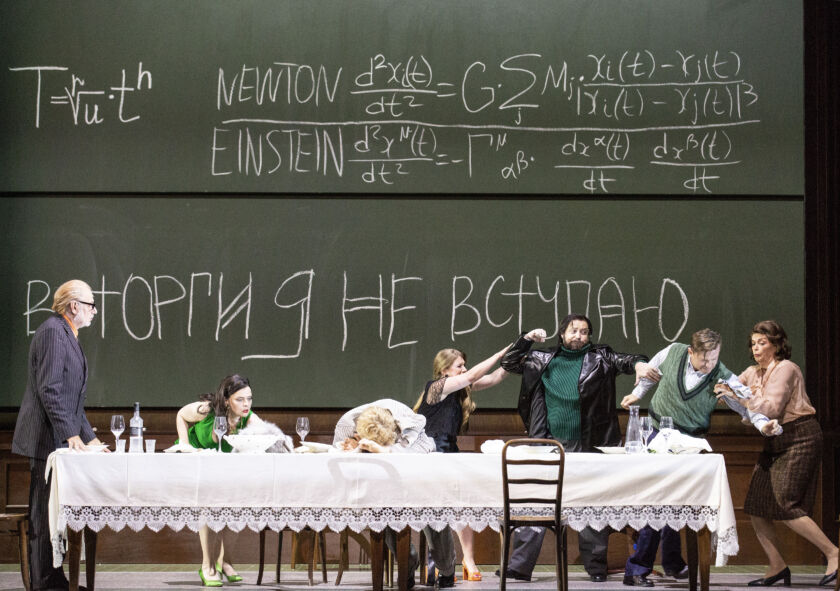

The Idiot and the Gambler. Returning from a stay at a Swiss sanatorium on the train, the young Prince Myshkin stumbles into a web of relationships surrounding beautiful Nastasya. Nastasya is adored by the merchant’s son Rogozhin, who is piqued by the fact that she immediately shows an interest in Myshkin. The latter, the well-meaning “idiot”, cannot deal with the love proud Aglaya feels for him, preferring to save Nastasya, whose suffering he intuits. In the end, only death and madness remain… “It is just like the novel,” Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla is convinced: “As soon as you’ve taken the initial hurdles, the opera opens up this fascinating world. Of course Weinberg’s musical idiom is similar to Shostakovich’s, after all he was enthusiastic about Shostakovich’s music even as a young man, and later, when they became friends, they showed each other their works. Today, however, the assumption is that it was Shostakovich who was influenced by Weinberg, more than vice versa – especially regarding the use of Jewish folklore.” Not only Weinberg himself, his Idiot also only really achieved fame after the composer’s death: as late as in 2013, the work saw its first full performance in Mannheim; this year marks its first outing at the Salzburg Festival. Krzysztof Warlikowski is the director, bringing his experience at the Felsenreitschule to the staging; the central roles will be sung from 2 August onwards by Bogdan Volkov, Ausrine Stundyte and Vladislav Sulimsky, most recently celebrated in Salzburg as Fenton and Ferrando, as Judith in Bluebeard and as Macbeth, respectively.

„The game demands that one loses in the end. Anyone who goes through life as a gambler will learn this, inevitably.“

Was it the financial constraints caused by the prohibition and foundering of his magazines and other factors which led Dostoyevsky to visit the Wiesbaden casino on his second European journey in 1863? At any rate, this was where his gambling addiction broke out – it was to keep a stranglehold on him for many years. When he returned in 1865, he quickly lost the rest of the 3,000 roubles for which he had signed over the rights to his entire work thus far to his publisher. The only way to redeem his debt was a new novel, which had to be written within a few weeks. He hastily began to dictate a kind of self-portrait, entitled The Gambler – and the shorthand typist he hired, Anna Grigoryevna, without whom he would never have completed the work on time, later became his second wife. The novel is set in the fictitious town of Roulettenburg, where the paths of a debt-strapped Russian general, his soon-to-be impoverished rich aunt, his arrogant and abandoned stepdaughter Polina and the private tutor Alexey, the title character, cross. When Polina confesses her affection for him, Alexey wins a huge sum by betting his last cent. His gambling addiction, however, soon proves more powerful than love…

A Piece about Us. The house always wins: that might also serve as a metaphor for life under Stalinism. When Sergey Prokofiev, still a student, made a plan to set to music Dostoyevsky’s Gambler, however, Tsar Nicholas II was still on the throne. When the work was ready for performance, the February Revolution of 1917 prevented its premiere. Prokofiev moved to the West, but failed to find the happiness and success he had hoped for. In 1929, he revised The Gambler for Brussels, where the world premiere was able to take place. In the Soviet Union, the opera was initially not performed because Prokofiev was considered an enemy of the system, due to his emigration; after his return due to disillusionment and homesickness, the work was incompatible with the ideology of “socialist realism”. The fatal omnipotence of money, the selling of souls, the end-time atmosphere – none of it jibed with life under what was supposedly the best of all possible political systems.

Musically, Prokofiev frames the action within a strict declamatory style: the atmosphere, dramatic and heated from the start, and the innumerable rhythmical patterns, which may have sonic directness, but are subtly graded, lend the piece great urgency. Finely chiselled lyrical moments and motifs are embedded within the composition, dissolving in parlando.

The music, which develops uncommonly rapidly, makes enormous demands on the singers’ concentration. Under the baton of Timur Zangiev, also making his Salzburg debut, Asmik Grigorian and Sean Panikkar are heard as Polina and Alexey; Peixin Chen sings the general and Violeta Urmana the role of Babulenka.

“The game demands that one loses in the end. Anyone who goes through life as a gambler will learn this, inevitably. However, we live in a world of extremely fatuous behaviour,” says Peter Sellars, the American director of this new production of the Salzburg Festival at the Felsenreitschule. Yet he also feels a melancholy longing: “On the one hand, the alarming dissonances of the Second Symphony, on the other, the children’s melodies of Peter and the Wolf – the only composer who had that kind of range that I know of was Mozart: someone who could write highly intellectual music, charming, tuneful, immediately approachable music that kids love, and also shocking visions of other worlds of metaphysical vertigo. Prokofiev’s life is heartbreaking. He is a very positive, kind, generous figure in a world which is very oppositional. The opposition he felt throughout his life was enormous. His music is the beautiful inheritance of a man who didn’t have a marketing department behind him, as Stravinsky or Schoenberg did, which explained around the clock to the world that he was its greatest living composer. It is a strangely beautiful and also sad story that he returned to the Soviet Union just in time to witness the show trials in Moscow and a generally dark era – just when his music fulfilled itself, with light, love, friendliness and overwhelming hope.”

To Peter Sellars, there is no doubt: “Prokofiev’s Gambler is not an interesting Russian rarity. It is a piece about us. To put that on stage right now is a responsibility and a necessity.”

Walter Weidringer

Translation: Alexa Nieschlag

First published on 11.05.2024 in Die Presse Kultur Spezial: Salzburg Festival