In 1707 Handel was 22 years old and living in Rome, where his first oratorio, Il trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno, was written and had its premiere. Composed in two parts, it includes some of Handel’s most beautiful and expressive music, with extraordinarily complex passages for the organ (which Handel himself performed) and the violin (composed especially for the virtuoso Arcangelo Corelli, the leader at the first performance). For Handel, the work remained a sort of oeuvre à clef from which he borrowed for other works on no less than 30 occasions. Surprisingly, Handel also completely reworked the material twice: first at a distance of 30 years, when the title changed to Il trionfo del Tempo e della Verità; and again after a passage of another 20 years when, in a new English adaptation, it became The Triumph of Time and Truth. And so the work, which is among other things a meditation on time, traversed 50 of the 74 years of Handel’s life.

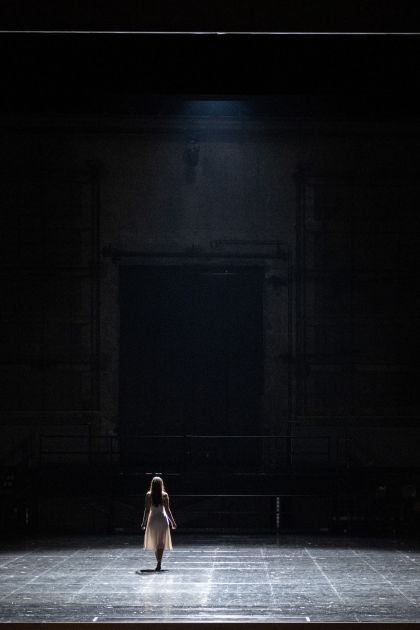

The libretto was written by Cardinal Benedetto Pamphilj (to whom the work is also dedicated) and is an allegorical psychomachia, a kind of dialectical debate, on beauty, truth, moral counsel, spiritual education and the ultimate triumph of time. The oratorio was created for Rome during a period when the Vatican was greatly opposed to secular dramatic works, but with its succession of superb da capo arias, duets and quartets it also possesses dramatic elements edging towards opera. Beauty (Bellezza), enjoying her reflection in the mirror of Pleasure (Piacere), swears to be true to Pleasure, but Time (Tempo) and Enlightenment (Disinganno) attempt to deflect her from her promise, reminding her that beauty is a flower that blooms only for a day and then dies. By the end of the oratorio, Beauty, following their guidance, rejects both the name and memory of Pleasure. Dedicating herself to the pursuit of truth, she frees herself from the superficial vanity of a life lived with and for Pleasure and learns to look towards a life of ascetic contemplation.

Il trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno can also be seen as another interpretation of the medieval Everyman theme, exceptionally well known to Salzburg audiences because of Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s version of the play, Jedermann. But this time, we are concerned with a young Jedefrau, which seems an appropriate enough character in this day and age for the development of what can be regarded as a kind of early musical Bildungsroman. The often consciously obscure libretto created by Cardinal Pamphilj for a work that was not intended to be staged offers an intense insight into human psychology. The principal theme seems to be that one has to search beyond surface appearances, discover and accept the truth about oneself and attempt to achieve balanced self-perception if one wants to live a developed and worthwhile life.

In the 21st century, much of the work’s specific theological dimensions are of less interest than the pressing subject matter announced in the title. Our production will attempt to examine what it means in a consumer-led, youth and beauty-obsessed world, constantly encouraging us to feed our appetite for vanity, self-interest and pleasure, to try and find the time to develop the enlightenment which can lead to spiritual fulfilment and truth. Bellezza’s journey from narcissistic self-satisfaction to selfless enlightenment takes her on a rollercoaster ride through her emotions, including anger, rejection, confusion, incomprehension, self-doubt and self-harm. It strikes me as an extraordinarily modern analysis of character, which could almost have come from the books of another famous Austrian: Sigmund Freud. It is the combination of cool moral guidance and intense psychological development that makes Il trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno one of Handel’s most powerful works and a thrilling challenge to stage.

Robert Carsen