Robert Carsen’s highly acclaimed production of Jedermann returns to the Cathedral Square for a second year with Philipp Hochmair in the title role.

Jedermann is a play that draws on the work of numerous generations of earlier artists, many of them unknown. It has been performed in the open air in front of the imposing edifice of Salzburg Cathedral for over a century in the irregular rhyming verse of Hugo von Hofmannsthal, a text that was inspired by the English morality play from the 1500s, which was itself related to an even earlier Dutch play.

Robert Carsen’s panoramic production locates Hofmannsthal’s ‘Play of the Rich Man’s Death’ immediately in the world of today, a world whose material values contrast starkly with the play’s underlying spiritual concerns. Here Jedermann is able to explain the complex workings of the financial system and is also capable of harnessing its dynamic forces for his considerable personal gain. He displays an evident sensual delight in being able to indulge himself in the best of everything that money can buy. He, it seems, is someone who really knows how to live. However, mortality intervenes while he is in his prime — and suddenly he is much less exceptional than he may have appeared. Deserted by those attracted to him by his wealth and largesse and faced with a task that no one else can perform for him, Jedermann is reluctantly forced into a process of self-examination. It is one that he finds disorientating, intimidating and entirely unsparing. And for those of us watching, the conclusion is hard to ignore: what can happen to him can — and indeed will — happen to us too.

David Tushingham

For most of us, death is something that happens to other people. And when death does come, as come it must, it will always be too soon. But why is that so, and, in holding on to life, what exactly is it that we are holding on to so desperately? Jedermann explores all that, and more. Its power and resonance come from the fact that, however codified the telling of the story may be, its subject matter concerns every single audience member, in every performance, every year.

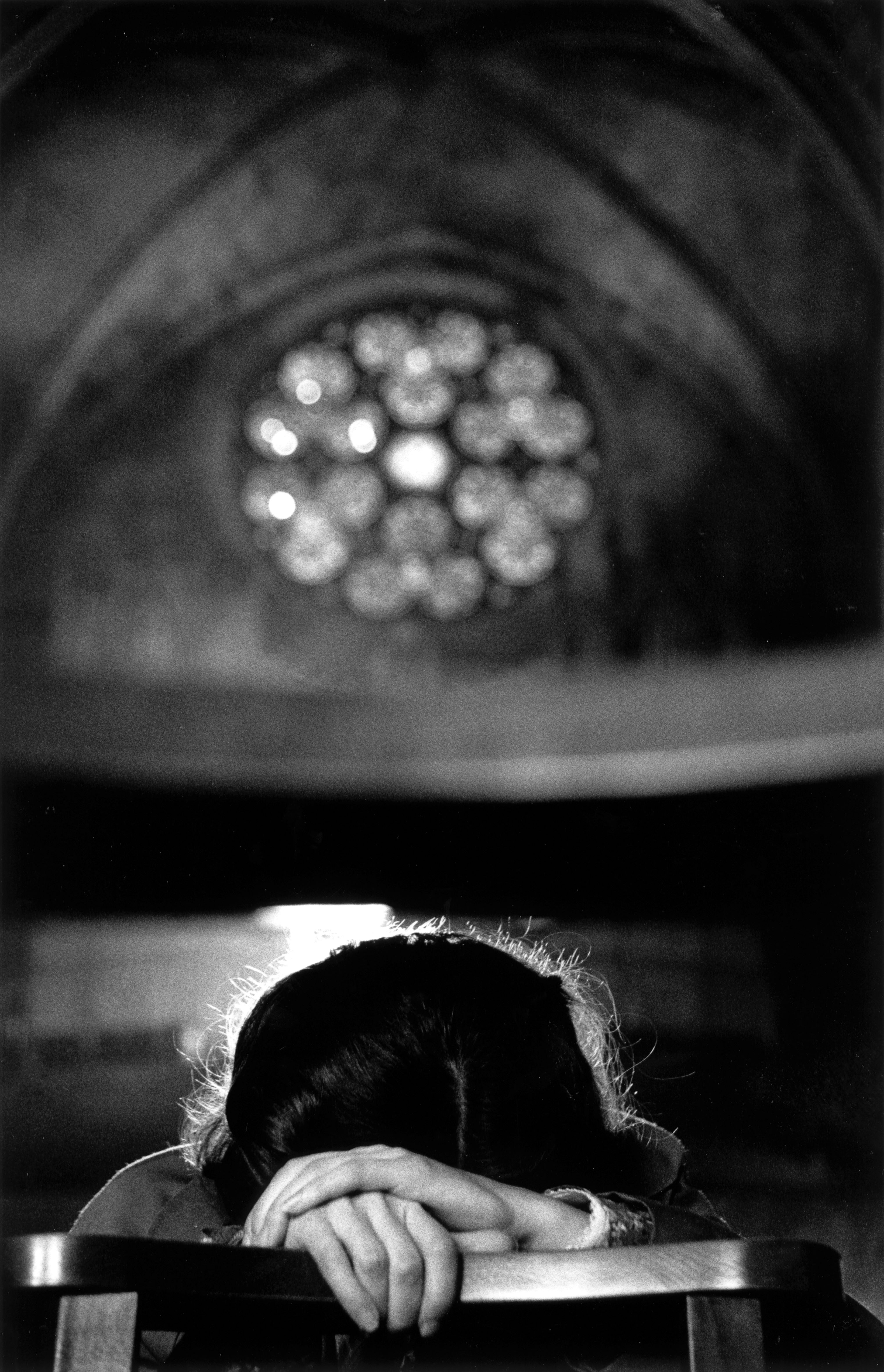

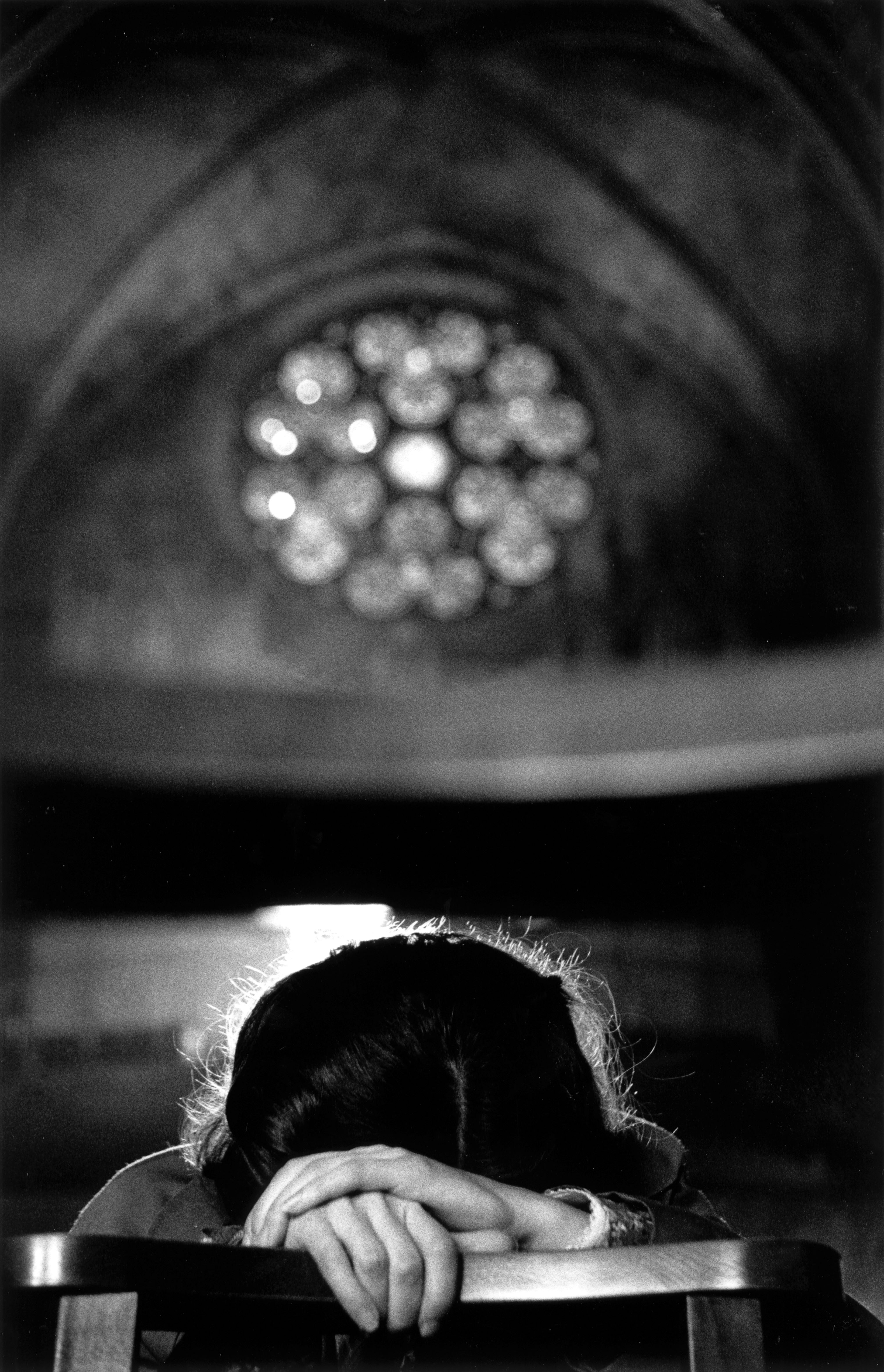

One of the most important developments that Hofmannsthal brought to the story is the fact that Jedermann begins to think about the possibility that something other than wealth and immediate sensory pleasure might be of importance before Death appears to him. Just after, or perhaps because of, the conversation he has with his mother, a crack appears in Jedermann’s psyche that causes him to question how he leads his life. And so, a search for the value and meaning of life begins, as Jedermann questions himself further about the meaning of Death, Good Deeds, Faith and, ultimately, God.

In his Jedermann, Hofmannsthal, greatly encouraged by Max Reinhardt, deals with the fundamental question of death, and the question of how — if at all — we can equip ourselves for it. Religious preparation for men and women of any faith can be essential, but I think Hofmannsthal also valued very strongly the relationship that art has to death. Art, which civilization after civilization shows us is the only thing that remains, can help us deal with, perhaps even cope with, the transitory nature of life and the finality of death. This is perhaps one of the reasons why Jedermann has become almost symbolic of the Salzburg Festival. Max Reinhardt’s idea that the play should be performed in the heart of the city, in front of Salzburg Cathedral, is an idea full of resonance, but also full of joy. We must not lose sight of the fact that although the play concerns the sacred, it is not sacred in itself, and I do not think either Hofmannsthal or Reinhardt wanted it to be approached as such. It is a celebration of life through an acceptance of death, like a christening and a funeral rolled into one. It is in itself a precis, a metaphor and an allegory of life.

Robert Carsen